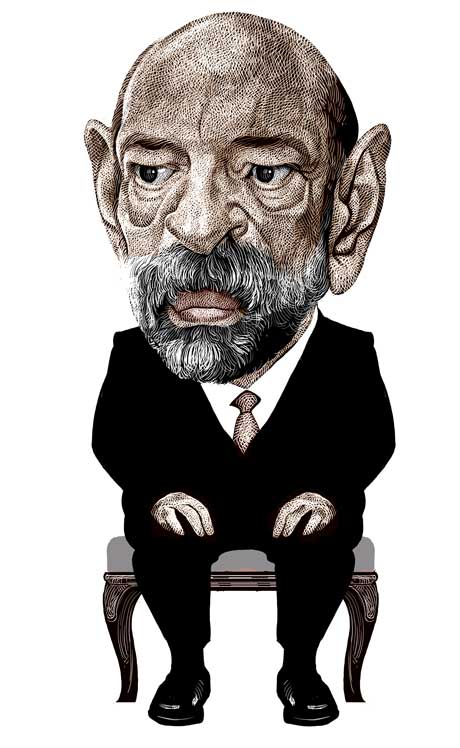

Ramachandra Babu/©Gulf News |

Depending on the source, Jordan’s new Prime Minister, Omar Al Razzaz was either born in 1960 — according to Reuters — or in 1970 — according to Wikipedia. That’s a ten-year discrepancy on a pretty basic fact, and somebody somewhere has either aged or shaved a decade off the man’s life. Either way, he has his work cut out for him, given the poor state of his nation’s finances.

If only that ageist somebody could shave a few billions of dollars off Jordan’s national debt, Al Razzaz’s job at hand might be a little bit easier.

Last Monday King Abdullah II appointed the former education minister to head the government of Jordan after accepting the resignation of Hani Mulki. Al Razzaz now must quickly find a way to de-escalate days of street protests that forced his predecessor from office over the government’s withdrawal of state subsidies on bread, and other tax measures. On Thursday, he took a solid first step in doing so, withdrawing a controversial tax measure.

So far, dozens of demonstrators have been detained and more than 40 members of the police and security services injured in the worst outbreak of widespread protests since the Arab Spring in 2011. The mob is angry now at the fiscal measures dictated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), who stepped in to assist the Jordanians in late August 2016. Then, it wrote a cheque worth $723 million (Dh2.65 billion), and now the IMF wants to see its recommended measures carried out.

Simply put, Jordan is deeply in debt. For every dinar in circulation in its economy, almost the same is owed to creditors, with its Gross Domestic Product to debt ratio now at the 95 per cent threshold. By 2021 the IMF wants this lowered to just 77 per cent — and hence the economic austerity and taxation measures introduced by the Mulki government.

In January, the government abolished subsidies on bread that had been in place and had left the price of the staple unchanged since 1996. Effectively pitta bread doubled in price overnight.

Other subsidies were withdrawn on 170 more basic commodities, making it much more expensive for Jordan’s poor to eke out an already precarious existence. Its unemployment rate is stubbornly high too, officially at 18 per cent.

The arrival of almost 700,000 refugees from neighbouring Syria has also placed a heavy burden on Jordan, and while many are housed in camps funded by international aid organisations and donor nations such as the UAE, those that don’t are a source for cheap labour that undercuts Jordanian workers.

Add to this volatile mix the fact that the IMF wanted income tax increases and the introduction of a sales tax and you get to see why those demonstrators were out on streets.

But is Al Razzaz the man to fix this mess and quell the protests?

On paper, he certainly appears to have all the necessary qualifications and experience.

He is a Harvard-educated economist who served with the World Bank in both Washington and the Middle East and is very familiar with the challenges of high debt levels and bloated public services faced by Jordan and its close regional nations.

His formal educational qualifications include a doctorate in planning with a minor in economic and post-doctorate work at Harvard Law School. Add to that a four-year stint as an assistant professor in the International Development Programme at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology between 2002 and 2006, plus another four years between 2006 and 2010 as the Lebanon country manager for the World Bank, and you get the picture pretty quickly that King Abdullah II has turned to one very smart cookie to set things straight again in Jordan.

Previously Al Razzaz served as education minister and oversaw plans to overhaul the country’s traditional state education system, drawing on generous United States and Western donor aid.

But crucially, he has been an opponent of the IMF-mandated reforms that hurt the poor. In this regard he has the good will of those protesters — Thursday’s withdrawal helps too — and Al Razzaz is expected to take a more gradual approach to policy changes.

Analysts note that his appointment and experience at the World Bank show that he is committed to reform measures — just not as quickly and severely as the IMF would like to see. That 77 per cent target on Jordan’s debt could be lowered while the 2021 deadline could very well be pushed back by several years to ease the pain felt by ordinary Jordanians.

Those who have worked alongside Al Razzaz say he has proven to be a capable administrator in a string of government posts in recent years where he worked on reforming the state pension fund. He also hails from outside Jordan’s traditional political class.

In appointing Al Razzaz to form a new government, King Abdullah II said that the cabinet “must carry out a comprehensive review of the tax system” to avoid “unjust taxes that do not achieve justice and balance between the incomes of the poor and the rich”.

The letter designating Al Razzaz as Prime Minister also said that “your government’s responsibility must be to launch the potential of the Jordanian economy … to restore its ability for growth and providing job opportunities.”

The day before, Petra, Jordan’s news agency reported that King Abdullah II warned his nation risked entering “the unknown” if it failed to find a way out of the current crisis.

Squarely, the responsibility for that has been handed to Al Razzaz — and it will require every ounce of his political skill, planning acumen and considerable economic experience to succeed. And right now, with the IMF 2021 deadline for reforms looming, time isn’t on his side — which is why Al Razzaz’s first move will be to play for it. He’s already proven to be adept at that — somehow, through somebody, he’s managed to juggle a decade on or off his age alone.

— With inputs from agencies