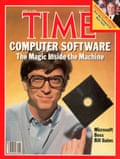

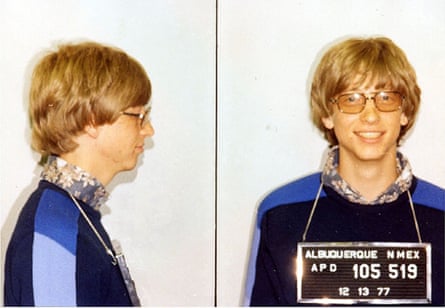

Bill Gates strides into the boardroom of Bafta in central London, pumps my hand and the clock starts ticking. It’s been noted before that, despite being the richest person in the world for a good chunk of the past 30 years, the one commodity he can’t buy more of is time. Gates has the same 24 hours in a day as the 7.9 billion rest of us. Today, I have him for 45 minutes, though in actual fact it will end up being just shy of 41. Those four minutes are, at least for the 66-year-old co-founder of Microsoft and the planet’s deepest-pocketed philanthropist, potentially huge.

Chit-chat bounces off him. Good flight? Gates, who is dressed in shades of blue from head to suede slip-ons, cracks open a Diet Coke, pops in a Halls extra-strong menthol lozenge. “Yes.” Did he come from Seattle? “I came in from New York last night.” Is he happy to be travelling again, and not doing these things over Zoom, or sorry, Teams? “I don’t think I’ll travel quite as much in the future. But some things still you want to be in person.” You don’t, I’m learning, almost eradicate polio with small talk.

Gates is in London today, Paris tomorrow, to promote his new book, How to Prevent the Next Pandemic. (Somewhat ironically, he appears to have caught Covid-19 on the promotional tour.) It’s not hard to find people who are sniffy about his credentials to hold forth on public health. He doesn’t hold a medical qualification, nor have scientific experience or training, as an army of social media users will remind you. On pandemics, though, Gates is something of a Cassandra. In 2015, during the Ebola epidemic in west Africa, he wrote a paper for the New England Journal of Medicine that pointed out the world was shockingly ill equipped to deal with an infectious disease that could cause a major global pandemic. He adapted the paper into a Ted presentation titled “The Next Outbreak? We’re Not Ready”, which predicted an airborne virus could cause 30m deaths and $10trn of economic damage.

That Ted talk has now been viewed 43m times – though, Gates notes wryly, more than 95% of those views came after Covid-19 came along. Meanwhile, the World Health Organization (WHO) recently estimated that the pandemic has already been responsible for nearly 15m deaths around the world. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has put the global economic cost around $14trn.

Gates could have written a book about this in 2015, but he accepts that not many would have read it. Even now, when you can reach millions through an online video, why does someone so tech-forward want to pour his energies into something as lumbering and antiquated as a book? “Well, an overall plan to be ready for a pandemic is not like a short news article,” Gates replies. “You need some background of what went right and what went wrong. Why did some countries have 10 times more deaths than others? There are all these claims about vaccines – are they the only tool that you need? Where did they fall short? And what about that first 100 days where you’re not going to have a vaccine: can you really stop transmission? So even doing that in, what is it, 240 pages? – it needs a book, not just, you know, a TikTok video.”

Besides, Gates, whose home library in Seattle has a domed roof and houses Codex Leicester, a collection of scientific writings by Leonardo da Vinci, just really loves books. “Most of the things I learn in depth, I either take a video course or I read a book; more books, but some video courses are very good,” he says. “So yes, I like embracing the full complexity of a topic to see what the path forward should be.”

Concise, urgent and powerful, How to Prevent the Next Pandemic makes a compelling case. Its central idea is that we need to establish a well-funded global organisation that Gates calls GERM: Global Epidemic Response and Mobilisation. It would be managed by the WHO, funded by governments (mostly the rich ones), and its scientists would be constantly scanning the world for any new outbreak. “Back-of-the-napkin”, Gates believes such a team would need 3,000 people and cost around $1bn a year. “We need to spend billions in order to save trillions,” Gates advises in a new Ted talk, “We can make Covid-19 the last pandemic”, which he delivered last month (currently 1.2m views).

What makes Gates think people will listen to him now? “Well, tens of millions of deaths, trillions of economic damage,” he says. “For many countries, it’s worse than either world war was and completely out of the blue. Huge costs and things that are even harder to measure: the learning loss, the mental depression. So it’s only rational to think, ‘Could we invest in avoiding this repeating itself?’ And I hope that, at least for a few generations, we’d be quite vigilant and willing to invest the billions that I suggest to save the lives and save the trillions this one cost us.”

Gates is, by nature, profoundly optimistic. He stepped down as Microsoft CEO in 2000 and, since 2008, has put his full energies behind the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The Chronicle of Philanthropy estimates that in 2021 the couple donated $15bn of their personal fortunes to the foundation’s work. This largesse has not been universally celebrated. Gates is routinely criticised for having too much influence, being a technophile and, at the wackier end, accused of benefiting financially from the pandemic and also somehow implanting movement trackers into vaccines. His personal life came under public scrutiny in 2019 when he was found to have had meetings with the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, and again last year when it was announced that Gates and Melinda French Gates were divorcing after a 27-year marriage.

The Observer had a huge – unprecedented, in fact – response to our callout for submission for this You Ask the Questions feature, from experts and 866 readers, and we rattled through as many as we could in 41 minutes. Gates clearly enjoys an intellectual challenge: he has a special smirk that he reserves for a line of interrogation that misses what he sees as an obvious point. He appears less comfortable when conversation drifts into personal areas and conspiracy theories, but he has presumably rationalised that this is the price he has to pay to make a meaningful impact in public health around the world, which he clearly feels he has.

“In our strategy debates, we move money around to where we can make the big breakthroughs and save the most lives,” he says. “Together with partners, that’s meant that we’ve gone from 10% of kids dying before the age of five to now less than 5%. And it’s clear that we can cut that in half again. So it’s very gratifying that innovation and even delivery in the toughest places is saving lots of lives.”

Devi Sridhar

Professor of public health, Edinburgh University, and author of Preventable: The Politics of Pandemics and How to Stop the Next One

What do you see as the biggest scientific breakthroughs for global health in 2022 that would save the most lives in low-income contexts?

If I had one wish in 2022, it’d be to solve malnutrition. So many kids never develop their brains or bodies fully, even if they get enough calories – globally, nearly one in five kids under the age of five are stunted, and in sub-Saharan Africa the figure is nearly one in three. Those are shocking statistics. Scientists are learning a great deal about the microbiome. Targeted therapies, while still in their infancy, could have an enormous impact on global health one day. So it’s a huge area, and I think we’re on the verge of some breakthroughs there. I also wish we had an HIV vaccine, a TB vaccine, but I’ll still put the solution to malnutrition at the top of my wish list.

Christina Pagel

Director of the clinical operational research unit, University College London

How does the presence of large, privately run international organisations active in the health arena, such as the Gates Foundation, impact on the ability (and funding) of the World Health Organization and similar bodies to coordinate a global response to a pandemic?

The World Health Organization needs to be funded by the rich governments. You have to count on the WHO to be there when a pandemic hits or coordinating all the different health work. Our foundation has ended up funding the WHO to improve their regulatory function, which was very slow and not good enough. So when we see things, we step up to help. But you shouldn’t have the WHO dependent on anything but the ongoing government donations.

Something that has a known end or hopefully a known end, such as polio eradication, it’s OK to take private money there. And we’re huge, we’re over 40% of the funding, that’s about $bn a year spent on that. That, with any luck, will come to an end in the years ahead. So it’s OK to have some dependence, but the WHO, that’s where the countries come together. And it’s always the countries who have all the control and all the votes, it’s their organisation. Frankly, I wish there were more foundation money. (It’s philanthropic money, not private money: private use means for-profit.) And I wish there was more philanthropic money going into these health issues. But you can’t depend on anything except governments.

Conspiracies often form around the rich and powerful. One that has long encircled you, having long-predated the pandemic, is your supposed part in corrupting the world’s vaccine supply as means of control, profit and, to a much darker extent, depopulation. What would your response be to these accusations?

Brandon Uddstrom, Pittsburgh

Well, I’m incredibly proud of the work that the foundation has done in partnerships with others to reduce childhood death. And the biggest single thing that’s been done is to get vaccines out to children in low-income countries. So for example, a diarrheal vaccine called rotavirus was being given to rich kids who are at no risk of dying of rotavirus and not to the poor kids at a time when rotavirus was killing more than 400,000 kids a year alone. And so by funding a lot of vaccine companies to make low-cost rotavirus vaccines, by helping to create Gavi [the Vaccine Alliance], the rotavirus deaths are now down about 80%. We’re still trying to get the coverage up to get those last deaths solved. Same thing for pneumonia, same thing for hepatitis C and HIV.

So vaccines are a miracle. And it’s mind-blowing that somebody can say the opposite. I’ve spent tens of billions on vaccines, I don’t make any money on vaccines. I have no idea why anybody would think that. I made my money on software. Warren Buffett’s money that funds the foundation was not made on vaccines, either.

What are your thoughts about the discussion of free speech on social media platforms? And would you consider becoming the owner of a platform?

Maya, Georgia, US

This issue is a real challenge, and I know that tech companies are thinking a lot about how to balance their products and features with the negative ways some people choose to use those products. There are important conversations happening right now between tech companies and governments. It’s not clear what the right solutions will be, but the dialogue is important. I’m hopeful that the generations who grew up online will help find solutions.

As for me, I have no plans to become the owner of a social media platform. I’m fully focused on my philanthropy and issues such as pandemic prevention, global health, climate change and Alzheimer’s research.

Jeremy Hunt MP

Chair of the health and social care committee

Are you worried that the war in Ukraine will cause world leaders to de-prioritise other key issues, such as tackling the climate crisis and preparing for future pandemics?

Absolutely. I mean, of course, we need to spend resources on Ukraine. But you have all the European budgets, all the rich-country budgets, let’s say, already pushed to the max by the pandemic. And that’s before they fund everything we need to do on climate change. So along comes Ukraine, which will increase defence costs, refugee costs, eventually rebuilding costs, they’ll want to subsidise the extra price of electricity, the extra cost of food. And so the challenges, the trade-offs in these budgets, are going to be tough.

I think it’s very important that we speak up, so that global health, things like the Global Fund [to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria] that’s saved millions of lives, or Gavi, that’s saved millions of lives, or whatever the pandemic-preparedness initiative [that is introduced], that we keep those in mind and not move on. The global-health enterprise is one of the most positive things humanity has done. To have it get fewer resources in this next decade would be tragic.

Anand Giridharadas

Author of Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World

Bill, do you agree with the notion that every billionaire is a policy failure? If we were to usher in a wealth tax that over time cut your fortune down to just below $1bn, do you think you would still be able to have a happy life, and do you agree that the resulting investments we’d be able to make – not to mention the cutting back of your power over public life as an end in itself – would make the world better off?

Well, I certainly think we can have much more progressive tax rates. And governments need more resources, including for things like foreign aid. I don’t necessarily agree, I think… you know, some money that’s spent on philanthropy can have an even greater impact than the average tax expenditure. But it is a surprise to me that tax rates in rich countries are not more progressive. I mean, only the US really has an estate tax, which of all the taxes is the most just, because it stops sort of aristocratic wealth, and these kind of dynastic fortunes at least get reduced pretty substantially. So why doesn’t Europe have an estate tax? A real estate tax? They don’t. And I guess democracies have chosen not to do that.

So, yes, rich people can pay more. I don’t think banning anybody being worth a billion dollars, that’s the right way to go about it. And it’s important to remember that, if you really want to grow social programmes, just do the numbers: you won’t be able to get that just from taxing the very rich. You can get more from the very rich, but if you really want governments to spend more, that’s too narrow a tax base for most things people would like to add, the social programmes people would like. So, it’s a numbers game. I’ve always pushed for more progressive taxation. That’s been on my website, and we’ll see: can the UK have more progressive taxes? Can any of the European countries? They don’t at this point.

You own a large percentage of US agricultural property and yet you often speak out against consumption of meat, particularly beef, and advocate for vegetable-based meat substitutes. Do you intend to eliminate livestock farming on your property and in the US generally?

Matthew H, California

Less than 1% of the farmland I own is used to graze livestock. The rest is used for growing crops. But somebody who is going to own US farmland over time will meet the idea: can you take cows and prevent them from being a source of greenhouse gas emissions? And there’s various innovations, including some I fund, to see if you can stick with cows and have lower emissions. I don’t know whether that will succeed.

Then, given that people aren’t going to give up meat-eating altogether, there’s probably a way of making meat-like products that, at some point, you might not even be able to tell the difference. And those work without greenhouse gases. If those end up being cheaper, and they have environmental and potentially health benefits, then they’ll succeed in the marketplace.

I help fund companies like Beyond, Impossible, Motif [FoodWorks] and a number of others that work along those lines. So 20 years from now, how’s meat going to be made? Innovation could help improve that. The way we kill cows, all other things being equal, you’d prefer not to have your food require that sort of animal killing.

Rachel Clarke

Palliative care doctor and author of Breathtaking: Inside the NHS in a Time of Pandemic

Is one of the greatest threats to human health today misinformation? How can we all do our bit to counter this?

The biggest killers around the world are HIV and tuberculosis. For kids, it’s malaria, and a variety of other health risks in their first 30 days of life. In well-off countries, controlling diet or having more exercise would dramatically improve health.

There’s no doubt that rumours and misinformation impact public health. It’s had tragic consequences during the pandemic. We’ve seen this in other areas of our foundation’s work as well. For example, we’ve known in polio eradication that rumours can cause families to refuse lifesaving vaccines for their children. That’s where accurate information – from health workers, traditional leaders, and other trusted community members –makes all the difference. We can all play our part by checking information we find online with reliable, trusted sources before sharing it with friends and family.

Michael E Mann

Director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University

You’ve said you don’t know the solution for the politics of climate inaction and also that we need a “miracle” to address the climate crisis. But the obstacles aren’t physical or technological at this point. Numerous researchers have demonstrated we can achieve the needed decarbonisation by scaling up existing renewable energy and storage technology, along with efficiency and conservation measures. The only real obstacle is having the political will to invest adequately in those technologies and put in place market incentives that accelerate the needed clean energy transition. Have you reconsidered some of your prior statements in light of that fact?

It’s weird to have… I mean, how do you think we’re going to make steel? How do you think we’re going to make cement? Most of the emissions are from middle-income countries. And the ability of either asking them to bear the huge premium and cost of clean approaches, or asking rich countries to subsidise that, that collective action problem is not likely to be solved with current green premiums. So it’s almost like he doesn’t acknowledge all the different sources of emissions. That’s weird.

He [Mann] actually does very good work on climate change. So I don’t understand why he’s acting like he’s anti-innovation. Where does he think the money is coming from? And how much money does he think it is? Is he telling India not to build shelter for their people? Anyway… I wish it was as simple as he was saying there: you just deploy what we have today, and everything will be super-reliable and super-cheap. But we’re not there.

Elizabeth Kolbert

Author of the Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History

Let’s assume the Covid-19 pandemic was the product of a spillover event. To prevent future, spillover-induced pandemics, do we need to change the way we treat animals?

Well, you can have fewer meat markets with the variety of species that create spillover risks. So, you can reduce that somewhat. But until population growth begins to slow, the overlap between humans and natural ecosystems is going up. And particularly as, due to climate change, animals seek cooler habitats, there’s a collision. We don’t have any tools to zero out the risk of zoonotic disease at this point. We have to assume that we’re likely to have more zoonotic diseases going forward than we have today.

Why did you spend time and dine with Jeffrey Epstein, knowing full well he was a convicted child sex offender? You seem like a good person who cares about people suffering from diseases such as Aids and malaria, yet why didn’t you give the same thought to the survivors of Epstein’s sexual abuse?

Ali Fleih, Michigan

Well, I had meetings with them and, at the time, I didn’t realise that would be almost viewed as condoning his behaviour. It’s still a mystery to me why the government didn’t take him on and make him pay more of a price for the bad things he did. My meeting with him is a mistake. I’ll always apologise. I thought, through his connections with various people, he would help me raise more money for global health. But, I shouldn’t have, I shouldn’t have met with them.

Vanessa Nakate

Ugandan climate activist

Alongside the vital emissions reductions, how do we ensure that financial benefits of clean technology and other climate solutions go to local communities, rather than rich investors?

In the end, I think the measure is: are people well fed? Are they healthy? Are the economies of low-income countries growing rapidly and catching up to middle-income status? And middle-income countries getting to high-income status? We have all sorts of inventions, like the measles vaccine, where the benefits to society are millions of times greater than to the people who invented those things. And so, we fund a lot of innovation, including seed innovation, that will help with the temperatures and droughts.

Africa is a particularly challenging continent. It’s the last continent left with meaningful population growth. The quality of governance in terms of corruption levels and ability to collect taxes to fund common infrastructure, including education and basic roads and a basic justice system, is very weak in Africa. Hopefully, the local populations work on that governance, and a lot of innovations – some from Africa, some from all over the world – are dramatically beneficial both in terms of climate and health results. Most medicines are sold at a COGS-type level [cost of goods sold] into low-income countries; we need to make that more widespread. Whether it’s climate technology or health technologies, no one needs to make anything from sub-Saharan Africa on any of those things. Those can all be done, justified and funded based on their their use in middle-income and high-income countries.

Should my grandchildren (12 of them, aged seven to 18) welcome or be afraid of the rise of artificial intelligence?

Penny Faust, Oxford

I’m excited about artificial intelligence and would most likely be working in that field if I were starting a career today, but I also believe that we need to be cautious and thoughtful about how to build it in the way that will be most beneficial for the world. Microsoft and OpenAI and other partners are taking a smart approach. There’s no doubt that advances in AI and machine learning are making enormous progress in health possible. AI can sort through data much more efficiently than humans and analyse inherently complex systems. When it comes to pandemics, we can now use computers to identify weak spots on pathogens. This will also help the world find new treatments for new diseases much more quickly in the future.

Tim Spector

Professor of genetic epidemiology, King’s College London

What are your thoughts on using a simple global surveillance tool based on symptoms and cell phones such as the Zoe Covid app to track and monitor future pandemics?

Well, there’s poor people without cell phones. So yes, we can do data gathering from cell phones. But we need diagnostic machines, we need genetic sequencing and samples. We have to create healthcare systems that work, independent of pandemics. If you want something to be ongoing behaviour, it has to have meaningful health benefits in non-pandemic years. And diagnostic machinery like the LumiraDX [a portable instrument that aims to deliver lab-comparable performance and real-time results] and DNA sequencing machines such as the nanopore allow us now to get very sophisticated diagnostics out to the primary-healthcare level, even in Africa.

We funded the pathogen genomics infrastructure in Africa during Covid. And we worked with [the US biotechnology company] Illumina and others to get those machines out there. And it made a big difference in terms of all the variant tracking: Beta was detected because of vaccine trials we had funded in South Africa. Then, later, Omicron’s discovered because of the pathogen genomics machines that have gotten out there. So I agree that we need better surveillance tools. But it’s not just patients directly using a cell phone, it’s a lot more sophisticated than that.

Thomas Piketty

Economist and author of Capital in the Twenty-First Century and A Brief History of Equality

Hello, Bill. Last time we talked in 2014, you told me you were opposed to the idea of a progressive wealth tax and favoured a progressive consumption tax. Between 2014 and 2022, global billionaires have more than tripled in size; eg, at the very top of the list, top wealth holders owned around $50-76bn each in 2014, and they now own around $200bn or more in 2022. This is obviously a much faster growth rate than the growth rate of world GDP or the average income or average wealth on the planet. Are you still opposed to a progressive wealth tax, or have you changed your mind?

Well, there’s only one person worth over $200bn (and it’s not me). The key point, though, is that rich countries, including the US, should have more progressive taxation. You [Piketty] have proposed a 5% wealth tax, but I think that would be very hard for governments to calculate and enforce, and I don’t think it has any chance of getting adopted. Other things that can raise a lot of money and have a chance of getting adopted include establishing or raising estate taxes, raising capital gains taxes, and making state and local taxes fairer.

I’ll pay whatever taxes people decide to impose on me. It might mean the foundation gets less money, which would be too bad, but whatever they decide. And in any case, I want the tax system to be way more progressive than it is today.

Beeban Kidron

Advocate for children’s rights in the digital world

Do you support California lawmakers bringing in protections for children to give them greater privacy and safety in the digital world?

Sure. I’m not an expert on the particular proposals, but that’d be a hard one to disagree with.

How much bitcoin do you own, if any at all?

Salman Basharo, London

I own zero. I’m not short bitcoin. I’m not long.

This article was amended on 15 May 2022. A reference to Gavi was misspelt as Gav due to an editing error.

How to Prevent the Next Pandemic by Bill Gates is published by Allen Lane (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply